Zhang Yue is currently the Head of Fundamental Science Department and an Associate Professor of Mathematics and Physics at Hainan Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences (BiUH). He earned his bachelor’s degree from the Yan Jici Honors Class at the School of Physics, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), and received his master’s and Ph.D. from the University of Utah in the United States. He later conducted postdoctoral research at the Institute of Nanotechnology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany, where he was awarded the prestigious Humboldt Research Fellowship. His research focuses on theoretical condensed matter physics and international science education. He has published extensively in leading academic journals, including around ten first-author papers in Physical Review B.

A Curious Explorer

When first meeting Associate Professor Zhang, he may not immediately come across as a typical science professor. Wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with an indie band logo and a relaxed smile, he carries the demeanor of an eternal explorer fueled by curiosity rather than academic formality. As he describes himself with three words—“naive,” “angry,” and “fun”—it becomes clear that he brings a distinct energy to both life and learning.

“Naive,” he explains, is what first drew him to physics. “Many great physicists claim they studied physics because it was ‘simple.’ That’s just not true,” he says with a laugh and a childlike sparkle in his eyes. “I’ve just always been extremely curious—I keep asking ‘why?’”

This sense of wonder carries over into his everyday life. He fondly recalls reading Mickey Mouse comics in his youth and still enjoys trying new things—like when he enthusiastically took up surfing, despite falling off the board repeatedly.

“Angry,” to him, reflects his intolerance of injustice or inefficiency. “When I see something wrong, I have to speak up. Keeping things hidden won’t solve anything.” Though he says this in a calm tone, his words reveal a quiet but resolute sharpness.

As for “fun,” it is both a lifestyle and a guiding philosophy. He follows theatre productions, attends hip-hop concerts, and is learning to skateboard. “Becoming an interesting person is a form of spiritual practice,” he says.

Filtering vs. Nurturing

Associate Professor Zhang’s vibrant personality also influences his views on education. When comparing Chinese and international higher education systems, he offers a frank assessment: “In China, education tends to filter people out, while abroad it focuses more on nurturing them.”

He elaborates: “Domestically, the system is always selecting the ‘best.’ Internationally, educators ask students: ‘What kind of person do you want to be?’ Then they help them work toward that goal.”

This belief shapes his own approach to teaching. “Success isn’t everything. If students can be happy and gain something meaningful, that’s enough.”

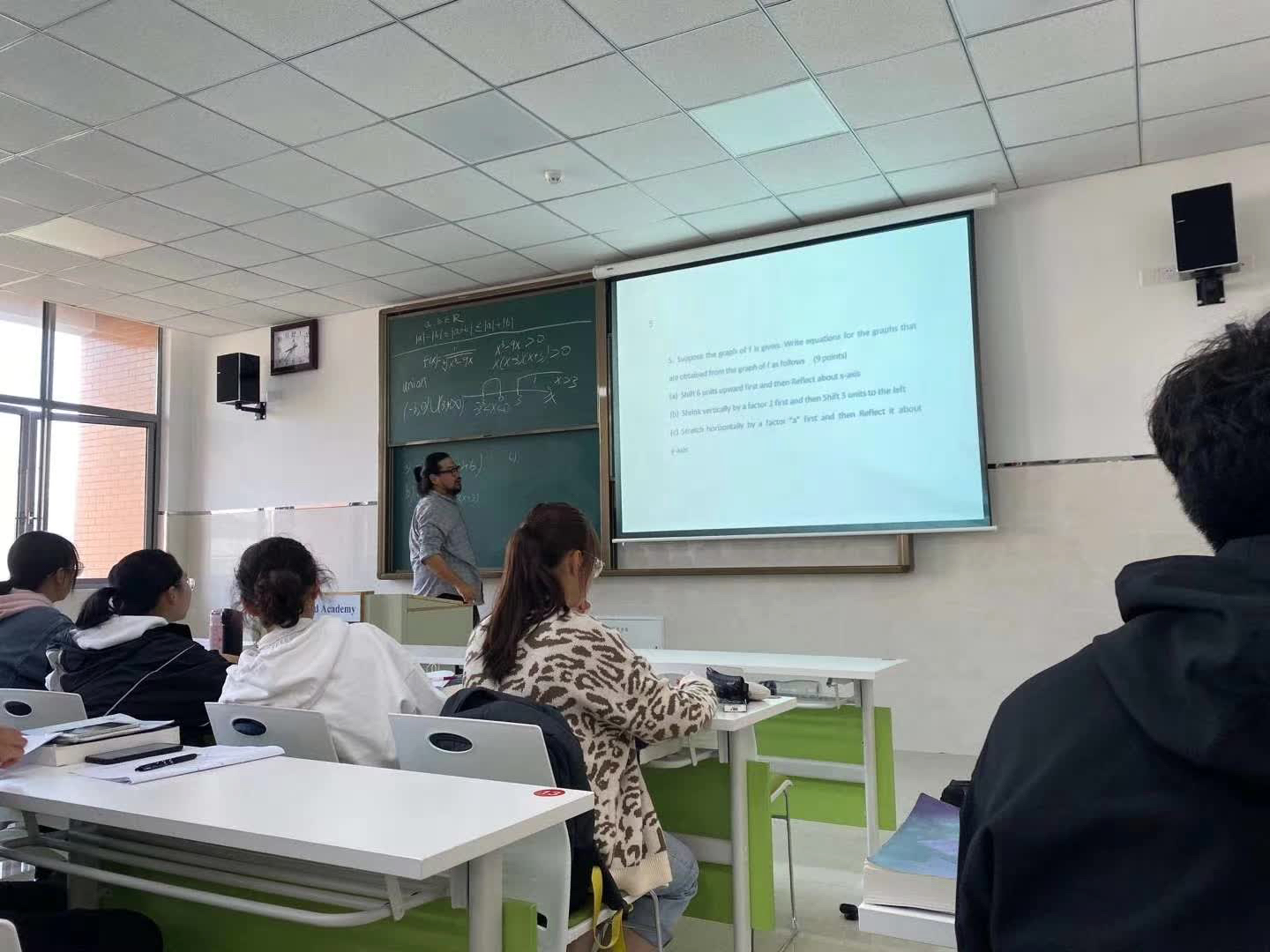

His classroom rarely revolves around KPIs, but often sparks discussions on the “useless usefulness” of knowledge. For example, in his physics lectures, he might move from explaining the reversibility of microscopic processes versus the irreversibility of macroscopic ones, to exploring the origins of life and the concept of time itself—guiding students to love thinking for its own sake.

As a theoretical condensed matter physicist, his field might sound complex, but he makes it engaging: “In simple terms, it’s the study of how large numbers of particles behave together—like in solids and liquids. That’s basically 70–80% of all physics.”

As a theoretical condensed matter physicist, his field might sound complex, but he makes it engaging: “In simple terms, it’s the study of how large numbers of particles behave together—like in solids and liquids. That’s basically 70–80% of all physics.”

In recent years, Associate Professor Zhang has become increasingly involved in international science education. He expresses concern about the utilitarian tilt in basic education: “We’re always asking what’s ‘useful’ to teach, but rarely ask students what they want to learn.” In his eyes, he’s just a “normal person” doing something slightly unconventional—like taking students on company internships not to teach them how to make money, but to help them realize that “what seems useless today may turn out to be the most valuable knowledge.”

On the hot topic of AI, he offers an insightful analogy: “AI is like a top university graduate—smart, but directionless. You need to give it a goal for it to be truly helpful.”

What research truly requires, he says, is logic, intuition, attitude, and taste. “Einstein came up with relativity, de Broglie with wave–particle duality—those discoveries were driven by intuition, not calculations.”

That’s why he encourages students to have their own preferences: “Do you prefer Sichuan cuisine or Shandong cuisine? Do you lean toward condensed matter or high-energy physics? Taste shapes direction.”

The Freedom to Educate

Associate Professor Zhang chose to settle at BiUH largely because of his fondness for Hainan—and his appreciation for the German philosophy of education. “Beijing is too dry; Hainan’s environment suits me better.” He had traveled frequently to Hainan since 2017 and had long been drawn to its climate and pace of life.

But it wasn’t just the location—it was the values of the institution that attracted him. “The university blends German-style rigor with educational freedom. It uses embedded learning—students work on projects in class and apply their knowledge in real companies. But we don’t revolve around ‘what companies need.’ We focus on the students.”

To him, internships are not just rehearsal for employment, but a way for students to apply knowledge and discover meaning. “What feels useless now may one day become your source of confidence.”

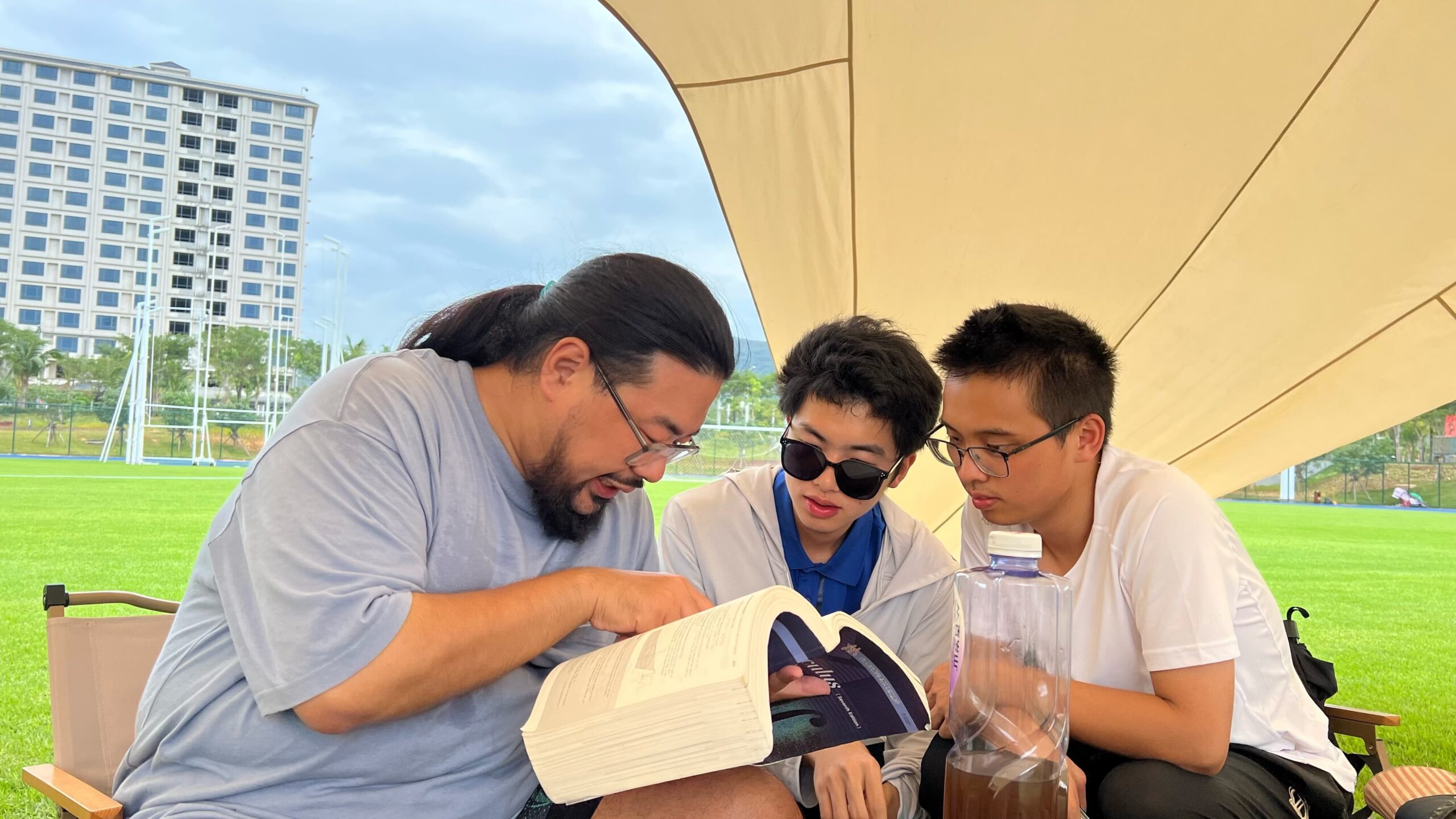

In his classes, unexpected moments abound—intense debates, surprise quizzes, field research trips. Students might be calibrating equipment at a tech firm one day, and the next, locked in a heated discussion in a lab over a single data point.

“I never pressure my students to ‘succeed,’ but I do hope they find joy through trial and error.” He recalls one student who used knowledge from condensed matter physics to solve a heat dissipation issue during an internship. “When they came back, their eyes sparkled like stars.” That moment of discovery, he says, was more valuable than any grade.

Today, Associate Professor Zhang continues to embrace life with energy and passion. His office is half filled with academic journals, and half with theatre ticket stubs and skateboarding gear. When asked about his expectations for students, he always returns to a simple wish:“Be happy. Learn something worthwhile.”